It’s not that he wasn’t a handy guy or didn’t like using them. The problem was he often couldn’t use them when he needed.

“My dad would hate buying power tools because I’d take it apart before he had a chance to use it,” Labbé said with a laugh. “When I had the opportunity to expand on that, I thought it would be a good thing to try.”

So he did. After graduating high school in Welland, Labbé, at the behest of his guidance counsellor, applied to the electronic engineering technologist program at Niagara College.

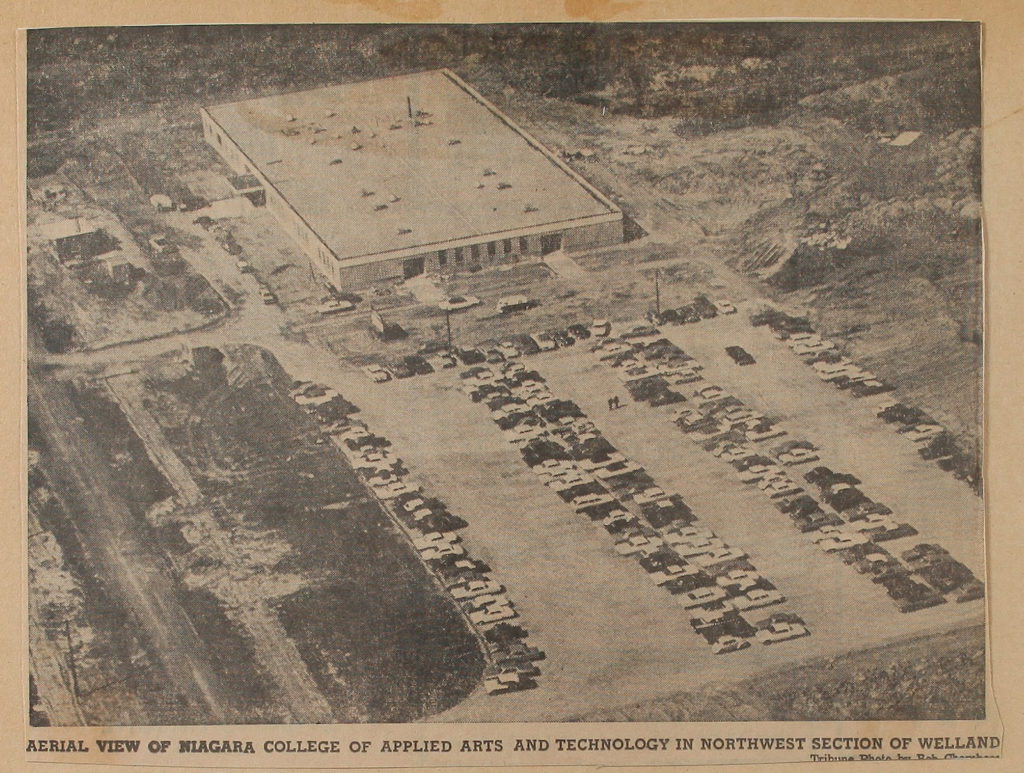

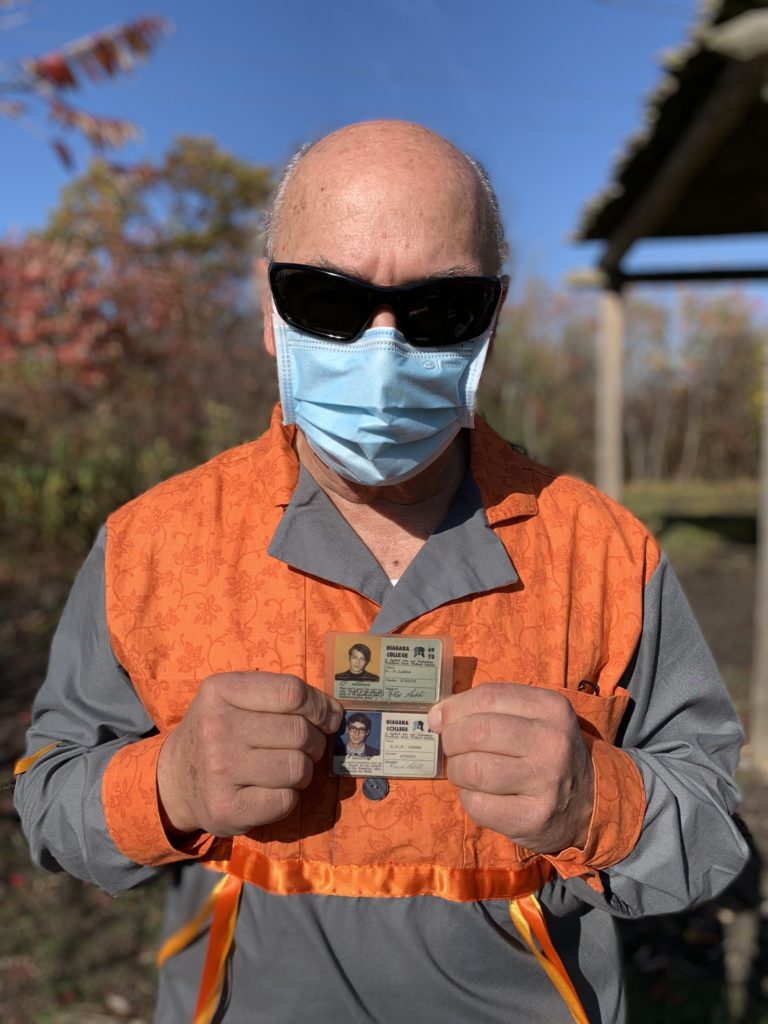

It was 1967 and this wasn’t simply another student enrolling in one of the college’s programs. Niagara College was just opening its doors as a post-secondary institution. When Labbé showed up to his first day of classes in the one and only building that made up the campus, he was one of 984 students to put his faith in NC and its not-yet hallowed halls.

Still, everyone in his program, Labbé included, knew the proverbial stakes were high as a community college in its infancy offering an engineering technologist curriculum based on one at an established Toronto polytechnic institute.

As a fresh-faced college student, Labbé was up to the challenges that would come his way during an intense schedule of classes. Some even required using a personal computer the size of a bar fridge and allowed students to keep ashtrays nearby for a mid-class smoke. Lunch breaks entailed visits to the cafeteria for 40-cent French fries that Labbé insisted he can still taste.

“I felt like a bit of a pioneer. It was something new for the Niagara Peninsula. We’d never had a community college and we were competing against everyone else,” Labbé recalled. “It was pretty intense the first year. We were pretty heavy duty. But the information was fabulous. The people were ideal. You couldn’t have had better faculty.”

Truth is, Labbé couldn’t have had a better guidance counsellor at Eastdale Secondary School in Welland, either. At least not a more prophetic one.

When Labbé came to him as a high school senior interested in working in a bank like his older brother, the guidance counsellor told Labbé he’d be better doing something technical or helping people.

The former held more appeal at the time, hence the decision to take a chance on Niagara and be part of its first class of students. After all, heavy industry dominated the peninsula and in nearby Hamilton. There was real opportunity for a career that allowed a kid who dismantled and reassembled power tools to capitalize on his aptitude.

Labbé would graduate in 1971 after taking a brief sabbatical to work at Page-Hersey Tubes in Welland. It was there he started to lament his choice of electronic engineering technology, wishing instead he’d gone into metallurgy after 10 months of being paid to test metal in the Page-Hersey lab.

With his diploma in hand, he would go on to don a lab coat at the Stelco steel plant in Hamilton, knowing his Niagara College education would hold him good stead regardless.

“No matter what industry you’re part of or work in, you’re always going to need electronics,” Labbé said.

He worked for Stelco on and off for 20 years, cutting and machining steel, freezing it, testing it, determining the conditions that made it thrive and those that caused it to fail. Then he decided to test his own mettle with a significant career change that his high school guidance counsellor could have predicted.

Labbé, who is Innu from Northern Quebec, started working as a powwow co-ordinator at the Fort Erie Native Friendship Centre in 1995. It was his dream job organizing the centre’s summer and mid-winter cultural gatherings.

His calling of helping people was getting louder, and if he didn’t hear it, his colleagues at the friendship centre did. A year later, he became the centre’s youth co-ordinator, topping up his hours managing the facility and doing maintenance —“whatever was available to keep me going.”

By 2004, he was running the youth program full-time as permanent staff. It wasn’t easy work but it was work he was meant to do, helping youth over the next decade — and young men, in particular — overcome alcohol and drugs.

“It was pretty intense and I was the only one (doing this) for the Niagara Peninsula,” Labbé recalled. “I thought, ‘Boy, I’m glad I didn’t do this in the beginning (of my career). This is rough.’ ”

Despite being stretched thin, despite the audible disappointment in his voice when he said “we still fell short” helping everyone who needed it, Labbé was dedicated to making the lives of his Indigenous brothers and sisters better.

“We fell short because we couldn’t process (people) quickly enough. There were wait times. People wanted to go to native lodges (to heal), not mainstream (rehab facilities) because they didn’t feel comfortable,” he recalled. “People were waiting one year for four weeks or six weeks at a lodge. That’s not enough time. For me, (recovery) is a lifelong thing. Don’t treat it as a cold.”

Despite the waits and need for space at lodges, Labbé often heard people describe the experience as being in an open-air jail. What they needed more than a regulated system, he said, was a mentoring system.

An elder. Someone with wisdom. An old spirit who learned their lessons and could share them with others.

What they needed was Labbé, who had become known as The Eagle that Flies for his role finding and connecting the right people; for being an emissary every day for 12 years at the friendship centre.

“Sometimes you doubt yourself and say maybe you’re not supposed to be here, but you are,” Labbé said.

Emily Schutt never doubted Labbé. The Indigenous Student Success Leader for Niagara College worked with him in Fort Erie and formed an instant connection. Over the years, the two have become like family. Labbé is like a grandfather to Schutt’s young daughter, Freya.

“He’s just such a genuinely caring person,” said Schutt of the Tuscarora Nation. “Whenever he can help someone, he’ll drop everything to do it. He’s passionate about connecting with youth and connecting them with their culture.”

So when Labbé finally decided to retire at 70 from the hard work he was doing, Schutt immediately saw a place for him back at Niagara College, this time as a teacher — as an Indigenous elder who speaks with students, virtually during the pandemic and sometimes in person, and attending college ceremonies.

It’s the ideal role, Schutt said. Labbé is a strong male influence who takes an interest in everyone from the moment he meets them and easily finds common ground upon which to forge an icebreaking connection.

Take the Indigenous student from Saskatchewan, one of 360 Indigenous students from throughout Canada enrolled at the college. She was new to Niagara. But after a few minutes of meeting, Labbé and the student realized they had a mutual friend on the Prairies, Schutt recalled.

“It’s like ‘how do you know them?’ ” Schutt said. “That puts students at ease. There’s a genuineness and caring with those connections. When he connects with students, he acts like he’s known them their whole life.”

His gift for bonding aside, Labbé isn’t entirely comfortable with the responsibility that comes with the title of elder. Ask him what it’s like to be one and he’ll regale you with stories of others, younger and older than him, who he feels are truly worthy of the designation.

Still, there’s something to be said about being back at the college, coming, in a sense, full circle. He’s proud of his alma mater, no longer just a community college but an international one, he said.

Talking to students, Indigenous or international, is a highlight of his latest post.

“The school has changed and yet I don’t see a huge difference in the people there. The people seem happy there,” he said. “Some are from similar backgrounds. Some are miles apart. But by talking with them, they’re of a mind they’re in a better place than they were, and in Canada they’re in a good place. Niagara has a reputation. I know it does because they come from all over the world to be here.”

And 50 years later, he still draws on his own NC education. The way he was taught at Niagara is similar to how he imparts knowledge as an elder now.

“I started at 17 at the college. When I was there, I had never experienced learning that way,” Labbé said. “It was as close to Indigenous learning as I could put it at the time. Their methods, the way they applied the curriculum, a lot was left to the student because there was so much to teach.”

“When you learn, you should give it back to people who don’t have it,” he added. “You should share it. I have a much different perspective now.”